Part 1 of a 5-week series from the new Future of Making book by Tom Wujek. Stories will be posted here on In The Fold and on Redshift. To learn more about the book, visit www.autodesk.com/future-of-making-book.

LiDAR, drones, and other high-tech tools help create the first digital models of the stunning bamboo structures in Bali’s Green Village.

Shaan Hurley and Brett Casson awoke in Bali’s Green Village not really knowing what to expect. When they’d arrived the previous evening at this community of hand-constructed homes and a connected school, set along Bali’s Ayung River, they quickly recognized that they were somewhere unforgettable. Experiencing the breathtaking mansions of Green Village in the first morning light, however, with the audible ripples of the stream outside and the golden October sunrise literally streaming through the bamboo walls, still managed to be a mind-altering experience.

“It was absolutely amazing,” says Casson. “Nothing short of incredible.”

A fleet of drones did LiDAR captures as well as video and still photography, recording context, texture, and color.

The homes in Green Village are made almost entirely of bamboo. While this makes Green Village one of the more unique and sustainable communities in the world, it also poses challenges to its builders and architects. Modern architecture software comes loaded with tools that can simulate many different kinds of stressful events—windstorms, earthquakes, water damage, fire, and so on. But the bamboo houses in Green Village are built in such a novel way that testing their stability with standard architectural software is not really an option.

Hurley and Casson, both technologists for Autodesk, were in Green Village to capture comprehensive 3D LiDAR scans of two homes. Using the data they captured, Autodesk would be able to build models and simulations of the structures, which in turn would make Green Village’s bamboo architectural designs testable and, eventually, more stable.

That first morning, after the awe of the beauty of their surroundings wore off, Hurley and Casson looked around at the sweeping bamboo curves and wildly complex geometry of the building they had just awoken in, and quickly realized how complicated their work there was going to be.

“Seeing it in real life,” says Hurley, “just blew our minds.”

Hurley, in particular, was a veteran of extreme field-based 3D scanning projects: unsuccessfully dodging Portuguese man-of-war jellyfish while capturing coral reefs off the coast of Molokai; flying drones over stiflingly dusty Kenyan badlands to capture rapidly disappearing fossil fields; hanging upside down in SCUBA gear to scan the sunken USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor; mapping massive Washington mudslides; documenting the natural arches of Utah; and so on. But the Green Village job, set in an environment that many consider paradise, would turn out to be the most difficult—as well as the most rewarding—scan that Hurley and Casson had ever undertaken.

Bamboo palaces

The community of Green Village, in Bali, Indonesia, is curved and nestled into the lush, terraced slopes along the Ayung River, as if it’s always been there. Begun in 2010, Green Village now has 12 completed homes, plus 64 additional freestanding structures, some of which constitute the Green School, which is one of the most extraordinary primary schools in the world.

The “green” in Green Village refers to the values held essential by the people who live there, and of those who built the village. The entire community has been master-planned as a model of uncompromising sustainability—and breathtaking beauty.

The buildings in Green Village are designed by a local Balinese company called Ibuku. Ibuku (the name means “Mother Earth”) was founded by Elora Hardy, who acts as Ibuku’s creative director.

The Green School, a private school for about 400 students, emphasizes environmental stewardship. opposite bottom: The campus has grown to more than 75 buildings since its founding in 2006, and produces some of its own electricity via solar panels.

Hardy grew up in Bali but left for high school in California, then art school in New York, and eventually became a print designer for Donna Karan. After a few visits back to Bali, however, and seeing what was happening at the Green School that her father, John Hardy, had cofounded, she decided to quit her job and move home. “I recognized that something unique was going on at the Green School,” she says, “and I wanted to be a part of it.”

The success of the Green School created a demand for similarly sustainable housing nearby. The first two houses in Green Village were already in the planning stage when Elora Hardy arrived. “I had no agenda around being involved in building or construction,” she says. “But I was interested in spaces, and making spaces more beautiful.” To Hardy, beauty and sustainability go hand in hand, and Green Village was an opportunity to channel her passions into what would become—at least to date—a game-changing and unforgettable life’s work.

The magic in the models

The bamboo varietal Ibuku uses to build Green Village is massive. Called Petung, it is not the bamboo pandas munch on, nor anything like the weedy shoots you might see in your backyard. Mature Petung shafts easily achieve the heft and size of construction-ready lumber, reaching up to four inches in diameter, with a tensile strength equivalent to that of steel. Probably most important to the Green Village community, however, is that bamboo is almost ludicrously sustainable—reaching a building-appropriate size and strength after only a few years of growth. And it grows all over Asia.

But because an Ibuku home is built with bamboo and is essentially hand-constructed on-site by local craftsmen, it doesn’t lend itself to the software-based tools used by most modern architects and builders. Ibuku’s designs are hardly primitive, however. They are deeply complex, deeply considered, and deeply planned. While Ibuku sometimes uses elements of CAD to begin their designs, for each structure they design and build, Ibuku ultimately crafts a series of small, handmade bamboo models. To test the strength of a specific design, Ibuku literally applies force to the model, sometimes even standing on it. When a design is approved, they deconstruct the model piece-by-piece and cut the structure’s real-sized bamboo timber to match the scaled-up measurements of every little piece in the model. There are no formal blueprints and no software-generated renderings or plans.

Left: The traditional Ibuku method depends on scale bamboo models rather than CAD drawings. Right: Three of the handcrafted bamboo models that are used to test Ibuku structures and guide their construction. There are no formal blueprints, renderings, or plans.

Ewe Jin Low is the lead architect at Ibuku. Trained in England, and having run commercial architectural practices in Malaysia and Australia, he intendend, when he joined a few years ago, to bring more CAD and software into Ibuku’s design and building processes. And he still sees the value in testing structural design with software-based models. At the same time, however, he has been won over by the magic of the little bamboo models. His builders are craftsmen—not trained nor specialized construction professionals. The scale models are easier for them to refer to on-site, and they allow for immediate and tactile communication that can’t be achieved through computers.

“The bamboo models, and particularly the studio and site intercourse [they facilitate] between our artisans and architects,” Low says, “create the distinctive ‘wows’ that cannot be produced from CAD, for now.”

A cloud of mosquitoes

Because the models didn’t originate in the computer, the only way to get them there is through scanning—specifically LiDAR.

LiDAR, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging (or it’s a portmanteau of “light” and “radar,” depending on who you’re talking to), is a surveying technology that measures distance similarly to radar. Instead of bouncing radio waves off a target, however, LiDAR bounces light waves. Developed in the 1960s, LiDAR’s first practical application was in meteorology, measuring clouds. It gained fleeting global attention when it was used to scan the surface of the moon during the Apollo missions.

Because light waves have such a higher frequency than radio waves, LiDAR measurements are significantly more precise than radar. And LiDAR projects light thousands of times per second, adding even more precision. Unlike more traditional surveyor’s tools, LiDAR is nondiscrete, meaning it measures literally everything it sees, compiling millions of points of data—and therefore extraordinary detail—with every scan.

Casson once helped 3D-capture the Sydney Opera House with LiDAR. “Those sails would be absolutely impossible to do a very accurate capture of without the use of LiDAR,” he says. Only LiDAR could accurately extrapolate all the nuanced slopes, angles, and curves of the building, in three dimensions, and much more quickly than the months it would take with manual, discrete measurements. Using LiDAR, Casson and his colleagues knocked out that particular project at the Sydney Opera House in just a few days.

Hurley compares the point cloud captured by a LiDAR scan to a giant cloud of mosquitoes. Up close, it’s a random-looking mess. “But as you zoom out,” he says, “you can begin to make out what it actually is.” Stitch a few of those mosquito clouds together, and suddenly you can build 3D renderings of just about anything.

LiDAR captures a point cloud, made up of millions of data points. Shaan Hurley likens it to a cloud of mosquitos.

Because Green Village’s homes are built from bamboo, they don’t have traditional walls, traditional squared corners, or uniform surfaces. The bamboo used to build the structures—which can be up to six stories high—is almost always curved (because bamboo often grows curved, and because the homes in Green Village are purposefully built with curves to best conform to their surroundings). The floors are made of sliced bamboo, creating deeply ridged textures. The interior walls are also made of bamboo, and from the outside, you can literally see clear through huge portions of each home to the forest on the other side.

This makes the LiDAR capturing of Green Village’s structures very complex. Some of the light beams will hit curved outer bamboo walls and beams. Others will hit wildly textured furniture and interior structures. Still others will bounce off the beams on the far side of the house. Millions more will pass clear through to the forest beyond. Hurley’s cloud of mosquitoes just got much more difficult to stitch together into a coherent 3D model. In fact, the team had to place man-made spheres into the areas they were scanning simply to provide a set of easily identifiable landmarks that the 3D software could reference when compiling the data into usable point clouds.

Due to all this complexity, not only did the team have to choose the angles they scanned from very wisely, they also had to run significantly more scans to ensure they captured everything they needed.

What’s more, the structures in Green Village are designed to accommodate the surrounding landscape with minimal imposition. Many of the homes are built on stilts, and all are encroached by heavy foliage. Figuring out all the angles you need to scan is matched in difficulty by finding enough clear views of the structure to capture all those angles.

And that only covers the ground equipment. Getting a drone clear of the foliage—and the glimmering spider-webs of broken kite strings caught in the trees—was also a stressful challenge.

“When I saw Brett’s eyeballs, and the look of terror,” says Hurley, “it validated the fear that I was having. We had two weeks on the ground.”

The team got to work.

Working in double time

Hurley and Casson’s original task was to scan one house—a house alternatively known as the Ananda House and Dave’s House. But they were struck by the grandeur and beauty of the nearby Sharma Springs house, too—a five-story marvel that has been featured on magazine covers and in U.S.-based television shows. They decided there was no way they could leave Green Village, or really do Ibuku justice, without also scanning Sharma Springs.

It was a massive amount of work, far more than they had initially planned. Every piece of equipment had a specific job. The team began at 6 a.m. every day to get the Hovermap LiDAR drone up and down again before the winds picked up by 10 o’clock. They worked through the oppressively hot midday hours, then into the night, using a tripod-mounted Faro Focus X130 3D laser scanner for the interiors, and the Zoller + Fröhlich 5010c Imager laser scanner for exteriors. The Zoller + Fröhlich, in particular, was exhausting to work with, weighing 85 pounds without the tripod. It had to be lugged up and down five sets of spiral stairs every day. The team also found themselves perched on steep slopes with a ZEB-REVO handheld unit, one person operating the scanner and another holding onto him for dear life, to make sure he didn’t slip and tumble down the hill. But this smaller piece of equipment provided opportunities to scan from positions the larger scanner and the Hovermap couldn’t reach, and thus added significantly to the richness and thoroughness of the data. Finally, the team used two DJI Inspire 1 drones for video and photography to help add context, textures, and color, and help document the project.

Left: One of the LiDAR units, which are far more precise than radar. Right: Hurley and Casson’s drone fleet; each drone captures different kinds of data and images.

Throughout the project, all the equipment worked as advertised, even under the extreme conditions. The project was difficult and exhausting, but it was turning out—slowly but surely—to be a success.

A couple of weeks later, when they were finally finished, the sheer amount of data they had accumulated was staggering.

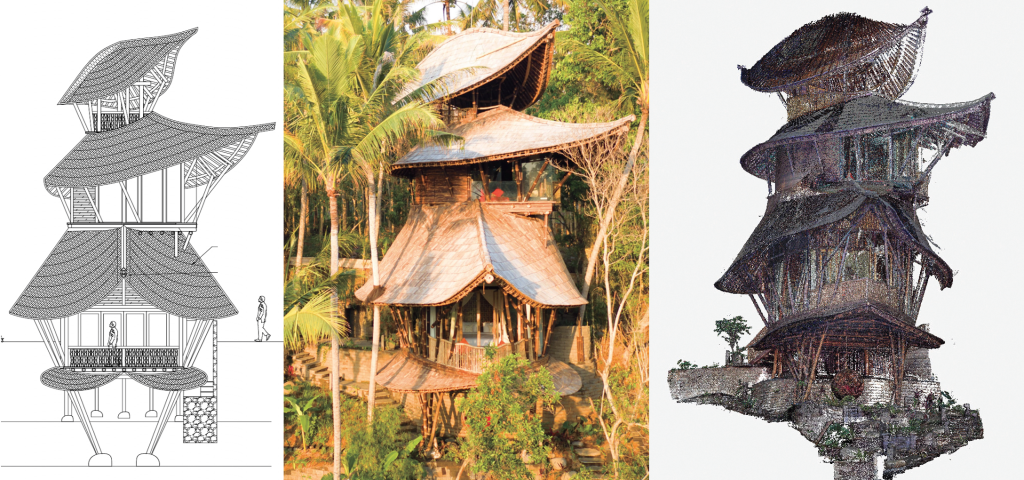

Three views of the project, from left to right: a traditional drawing; a drone photograph; and a LiDAR point cloud.

The Sharma House required 57 internal scans with the Faro Focus X130 3D laser scanner, and 18 external scans using the Zoller + Fröhlich 5010c Imager. The scanning was done in an astonishing 15 hours.

The Ananda House required 58 internal scans using the FaroFocus X130 3D laser scanner and 32 external scans using the Zoller + Fröhlich 5010c Imager.

Several additional terrestrial captures were completed using the ZEB-REVO handheld unit, which was primarily used to capture bridges and paths, and the Hovermap drone.

Potential and possibilities

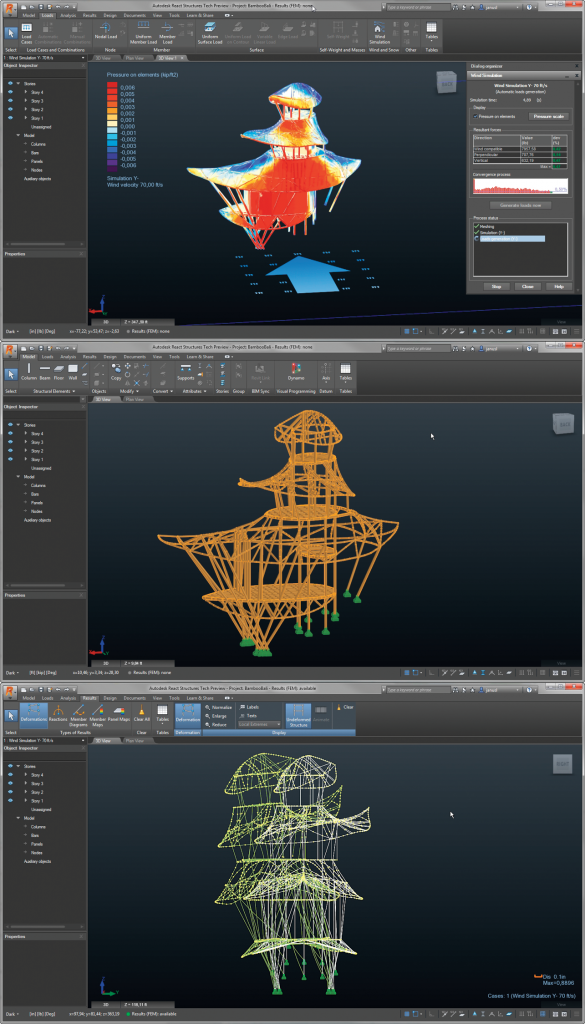

The Autodesk team had essentially captured the data needed to create intricately detailed digital 3D versions of the handmade scale models that Ibuku uses to design their structures. Hurley and his team are now working with those digital models to develop new simulations of the structures to test their resiliency and integrity under various types of natural duress. They’ve hit the Ananda House with hurricane-force winds, earthquakes, and other load-bearing events—simulations that aren’t possible using only the bamboo scale models—and shared their results with Low and the team at Ibuku.

The Autodesk team’s scans allowed Ibuku to create detailed digital models and drawings of the buildings. The top image shows a simulation of wind forces on the building, modeled from the data collected through the team’s scans.

Low is most intrigued by what they can learn from the wind models, and how it might affect their designs in the future. “We can just begin to imagine the potential and possibilities,” he says, “looking at structural loading and design and many other technical variables.” He imagines the simulations helping them with their design-safety factors and reducing waste on jobs.

But as a true convert to the Ibuku way, Low also cautions against an over-reliance on technology. “How do we harness today’s fast-paced technology and not let it overwhelm us, or take over too much of the main role that humans have to play here on Earth?” he asks.

That train of thought has affected how Hurley and Casson think about technology as well. “I do so many presentations to industry, talking about the virtues of the digital world, and I’m a deep believer,” Casson says. “But Bali made me really assess what craftsmanship means. It had a profound impact on me.”

Hardy, likewise, is excited by what the teams at Ibuku and Autodesk can both gain from the LiDAR project. It’s not just “what they will learn from what we’ve done,” she says, “but also that we will be able to be more assured, backed by an understanding of our engineering, to the depth and detail that can be captured.” She pauses for a moment, then adds, as though she is surprised by her thoughts all over again: “That’s incredible.”